Party Identification and European-American Political Views

2018-09-02

In a video last month, Sean Last takes on "The Myth of European Assimilation" by disaggregating white voting and earnings. In short, it's a good takedown of the default, overconfident narrative of American migrant assimilation. If your idea of 20th century immigration is wretched refuse coming ashore, moving their way up, and merging economically and politically into the uniform White America we know today, that pretty much didn't happen. By most measures, identifiable European ancestries are still differentiated within America, and in ways that parallel their differences in Europe. The story of white America, then, is less one of assimilation, and more of selection bias and attrition.

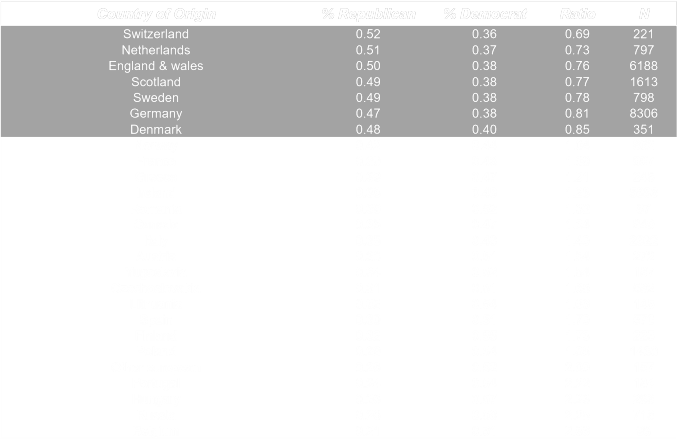

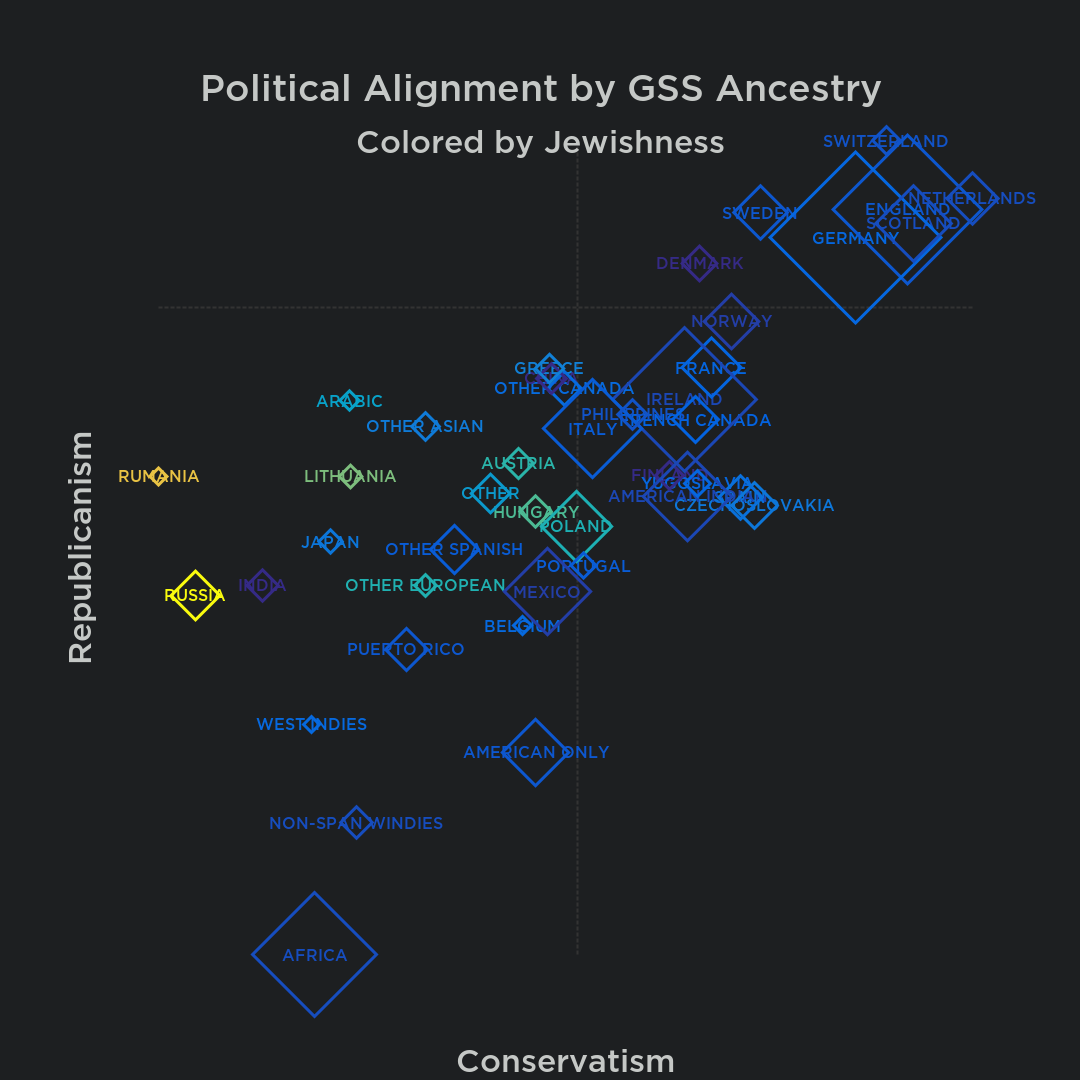

Last elaborates on party identification in Deconstructing the White Vote, posted at The Alternative Hypothesis. The main subject of discussion is apparent heterogeneity of the white vote, as he shows using the General Social Survey family ancestry question:

Here is the main result of the analysis:

Thus, only British, German, and Scandinavian Whites were found to identify as Republicans.

From this and other data, Last has come to see European politics as less distinctive than he once did, and has pushed back against a unified European nationalism as a goal in itself.

This will be a partial response to his argument, focusing on differences in party identification and views by GSS ancestry within America. I argue that party identification exaggerates intra-European differences, in comparison to non-European groups.

The Limited Picture of Partisan Politics

Political parties adapt to the landscape in which they evolve. In the United States, the political map is still mostly defined by white voters — 70% in the most recent election, and well into the 80s only a couple decades ago. (For comparison, the GSS data we're talking about span over 40 years.)

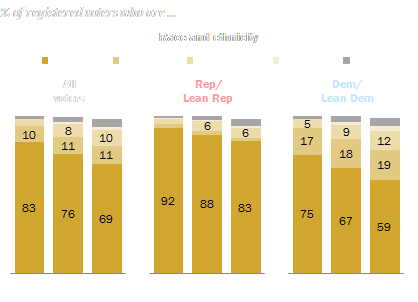

Overall, while non-Hispanic whites remain the largest share of registered voters (69%), their share is down from 83% in 1997. African Americans make up 11% of voters, a share that has changed little since then.

Excerpted from Pew Research Center.

White influence is further increased by historically stronger voter turnout and political engagement. The result is that party politics are well adjusted to the range of white opinion, which can cause some issues of perspective.

Limited Dynamic RangeIf the electorate were 100% white, white people would fill out the range of a party spectrum fitted to their diversity of opinion, however wide you think that is. In a white political system, there would still be contested elections, and sub-populations that lean strongly in one direction or another.

To the frustration of nationalists everywhere, the arrival of the first non-white voters does not immediately change this. Even if the minority voters have a distribution of opinion wholly outside the range of the majority group, the party spectrum cannot fully reflect this. Parties position themselves in an attempt to reach the median voter, and the party divide remains centered around the median even in the presence of a skewed distribution of opinion. The party adjacent to the minority group cannot adjust itself to fully represent them without ceding competitive voters at the center of the majority. The result is that party identification remains dominated by the incumbent majority, with the minority fitting themselves into their nearest party as best they can.

The implication is that party identification can misrepresent the relative diversity of opinion. The outlier group's partisanship is saturated, and its range compressed, in the same way a bright light appears blown out in a photograph exposed for a darker scene.

This effect is not perfect, as parties are not entirely uniform, and they can to some extent define themselves in different ways to different people. But it is probable that relative party lean among whites will differ dramatically in a 10% black electorate, vs. 30%, even if none of their opinions change.

Dimension ReductionIn measuring mental abilities, all metrics are correlated, which means that a single scalar value (IQ/g/etc) can be used to depict the relative position of individuals and groups without unacceptable loss of information. This is not true of political beliefs; There is (probably) no "general factor of politics" along which people are so cleanly separated.

Partisan identity is necessarily an inaccurate cross-section of a population, with potentially diverse groups being collapsed, their positions projected onto a new axis crudely spanning them as best it can. To continue the photography metaphor, partisanship is a greyscale representation of a color scene.

From my reading of party formation theory, the way this sorts out is that parties define themselves along the axis of greatest variation. People don't like being in the same party as those dissimilar to them, and this is the stable equilibrium that minimizes defections to the other side.

This makes possible a situation in which a minority group is qualitatively different from the majority, in a way not captured by the dominant axis of political identity. The minority population begrudgingly leans one way or another in the incumbent frame, but the full distinctiveness of their politics will not be felt until their numbers increase, and the partisan axis rotates to reflect this new diversity.

I believe both of these effects — suppressed differences of degree and kind — are at work in obscuring the distinctiveness of European politics within American party ID. But first, a necessary diversion.

Selection Bias Confounds Some Small Backgrounds

In conversation subsequent to Last, several eastern European countries have stood out as particularly Democrat-leaning, prompting some debate. The oddity of these groups became more apparent to me while attempting to fit GSS ancestries into my own crude Inglehart-Welzel map. Russians, among the world's most materialist peoples in the World Values Survey, were in America leaning towards postmaterialism, a striking reversal paralleled in several related ancestries.

When I retrieved religious preferences, to depict Protestantism, I noticed extreme Jewish representation among these backgrounds:

Highly Jewish GSS National Origins| Origin | Jewish Religious Preference |

|---|---|

| Any | 1.86% |

| Russia | 50.1% |

| Romania | 32.6% |

| Lithuania | 17.8% |

| Hungary | 14.0% |

| Austria | 10.9% |

| Poland | 9.4% |

These represent lower bounds of Jewishness, due to ethnic Jews not always identifying with the Jewish faith.

This accounts for some of their Democrat leaning (Russian-American in particular is practically synonymous with Jewish). Even where Jews are not so dominant a factor, their extreme overrepresentation is likely indicative of the selection bias present in emigration from these source countries. The next one million Russian migrants would not be so liberal.

Partisanship in Greater Detail

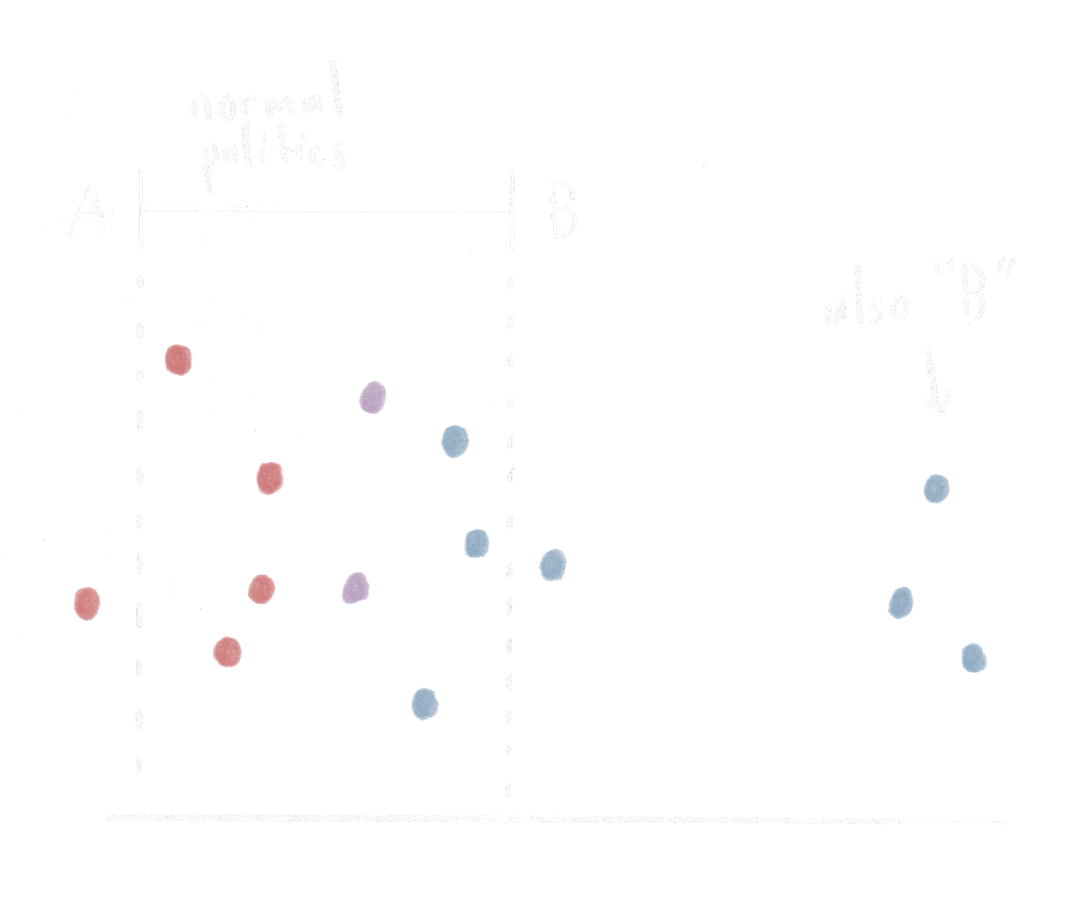

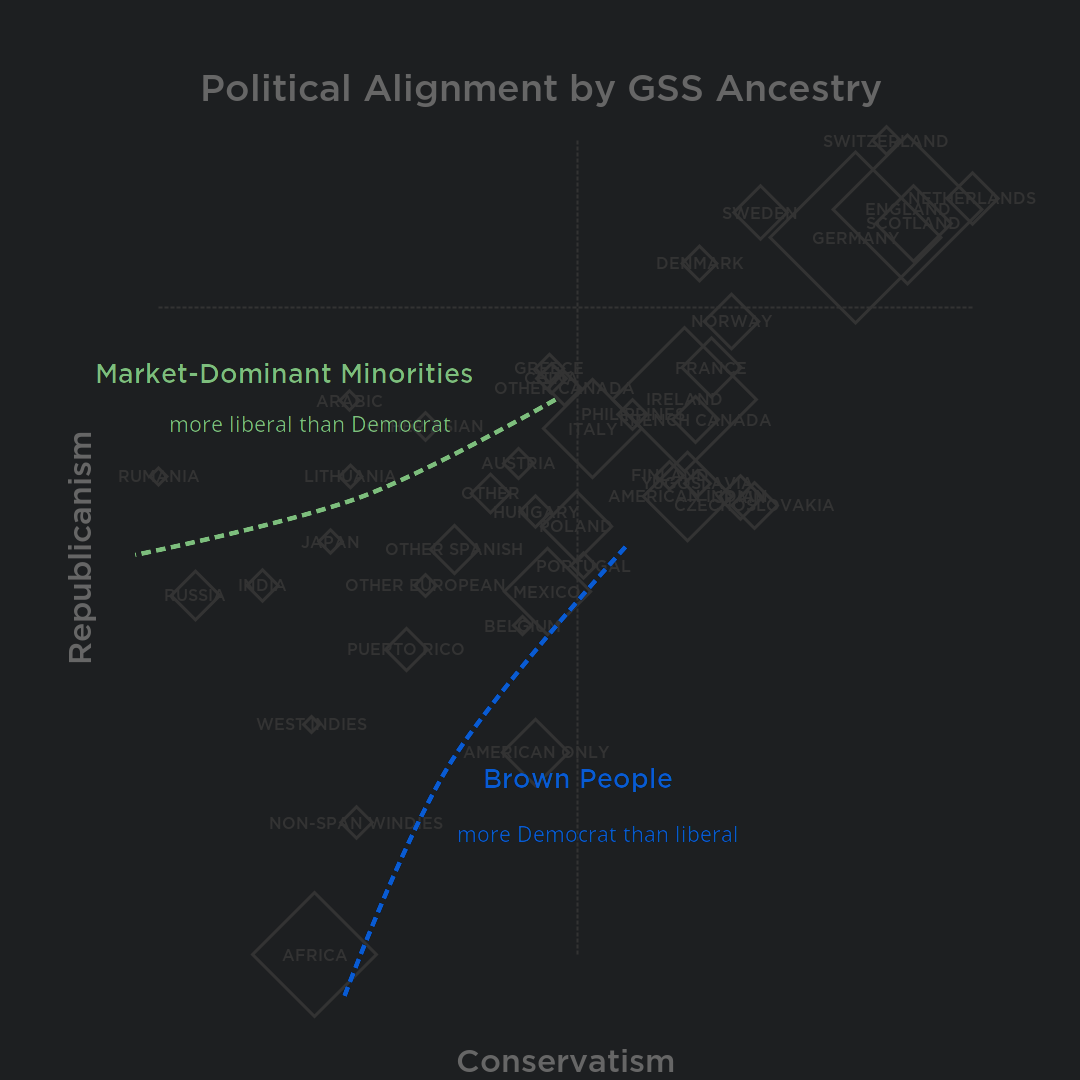

The GSS has two axes of political leaning, Dem/Rep and Lib/Con, which are correlated, but not perfectly so. Plotting them both, scaled by population size, adds some nuance:

Observations:

- Americans are uniformly more "conservative" than "Republican".

- Sized by population, the European spectrum doesn't appear to lean quite as liberal as one might glean from a table.

- It's apparent that the left-most European ancestries are mostly the small, highly Jewish ones. With these removed, there is much less inter-racial overlap.

- While the Republican core is strongly conservative and Republican, the left end of the spectrum is not so tight.

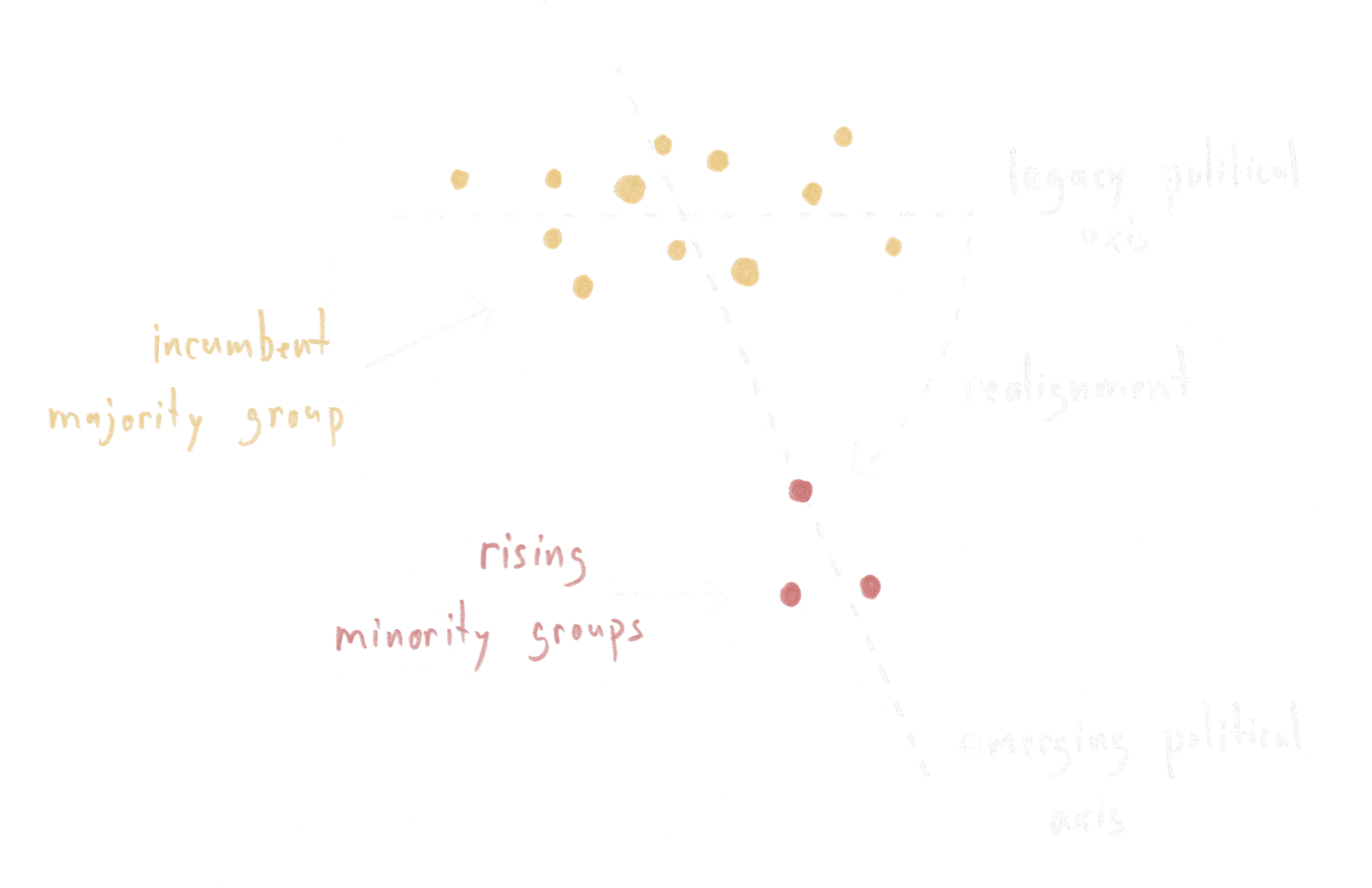

I see the fraying at the liberal end as dividing roughly into Jews/Asians on one side, blacks/browns on another:

As we know, blacks and hispanics are not exactly "liberal" in American political language. They're anti-market, and vote for transfers that benefit them, but also have some "natural conservatism" on issues that otherwise differentiate whites, such as religiosity and ingroup preference.

Policy Over Party

So European party ID isn't quite as heterogeneous as a crosstab would suggest, but it still blends into that of other groups. What do differences look like on actual policy questions?

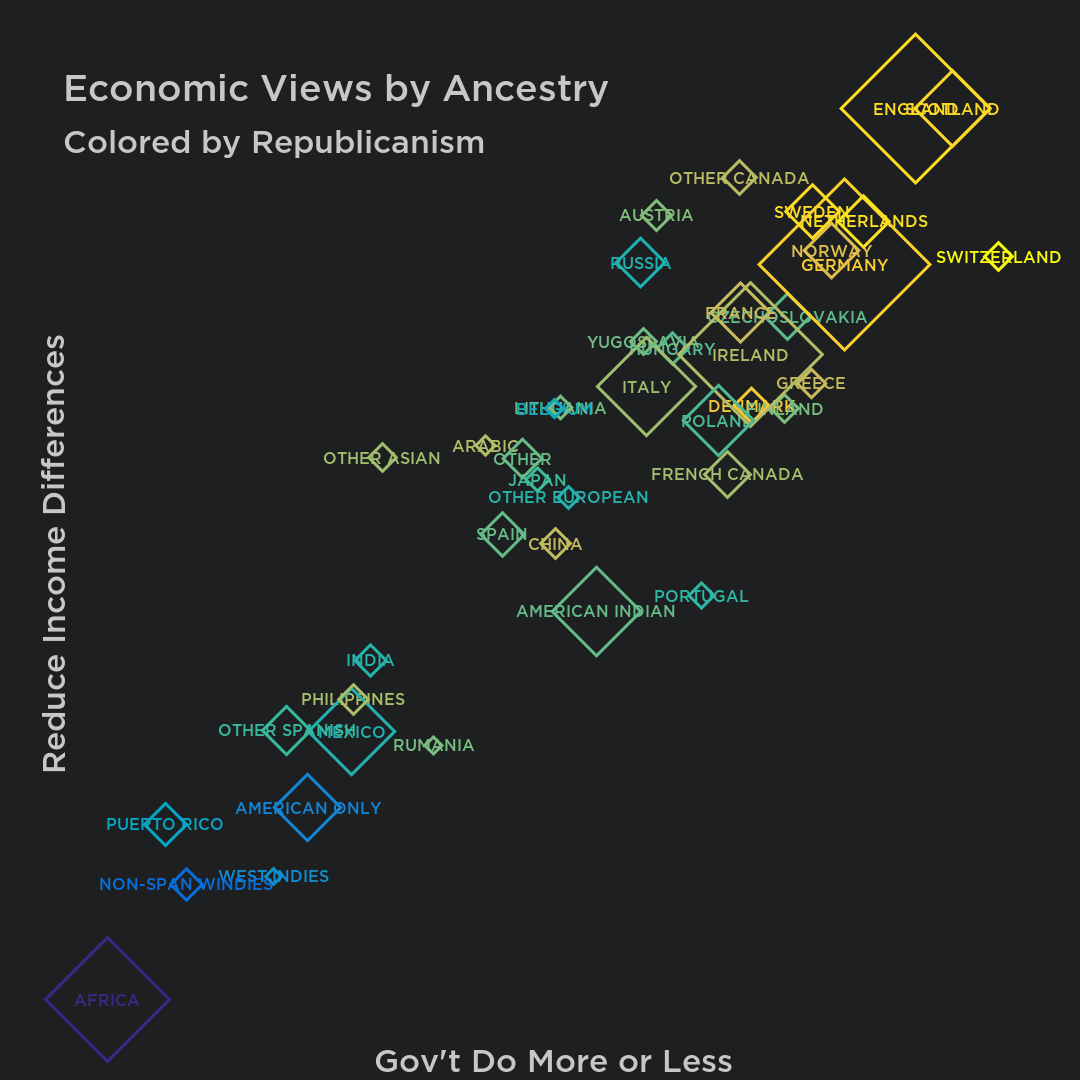

Two issues strongly correlated with partisanship are size of government and income redistribution:

Groups separate even further in this direction than partisanship would suggest. The smooth gradient of party ID, with Italy blending into Poland blending into Mexico, here shows a sizeable gap between the black/hispanic ancestries and Europeans. There is, however, overlap between more left-leaning Europeans and the several Asian-American ancestries.

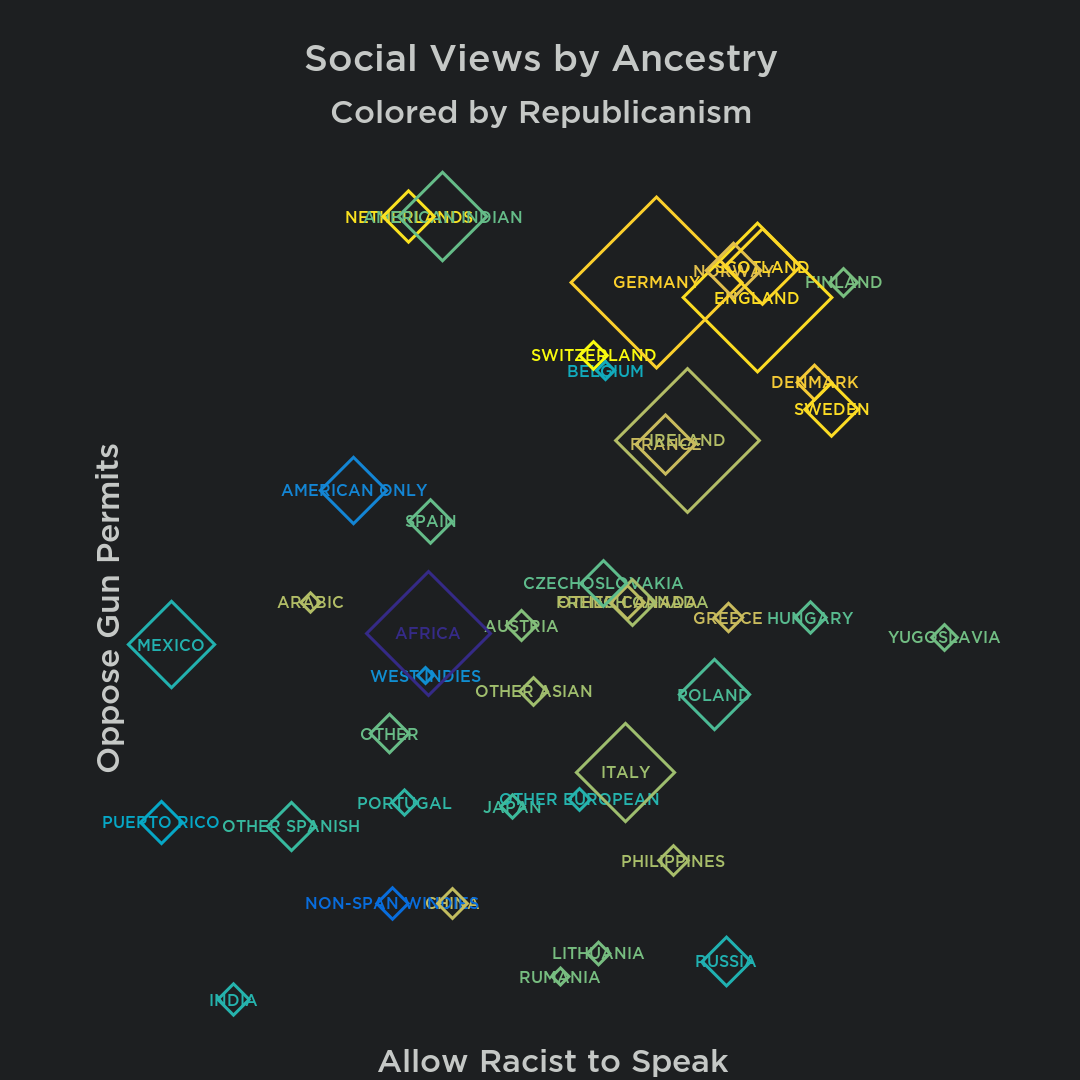

I also looked at two social questions of interest to me, which vary by party — support for (explicitly racial) free speech, and opposition to gun permitting.

In contrast to economics, personal freedom issues tend to be less correlated and ambiguously partisan:

- There's a clear western European concentration in the top-right, supportive of both guns and free speech.

- Jews stand apart from other Europeans as being favorable on free speech, unfavorable on guns.

- PoC tend towards the lower-left, but less uniformly so.

- Partisanship loosely moves in the direction of more Republicanism in the more permissive direction of both questions.

- Everything else is a mess.

Clustered Policy Views Distinguish Europeans

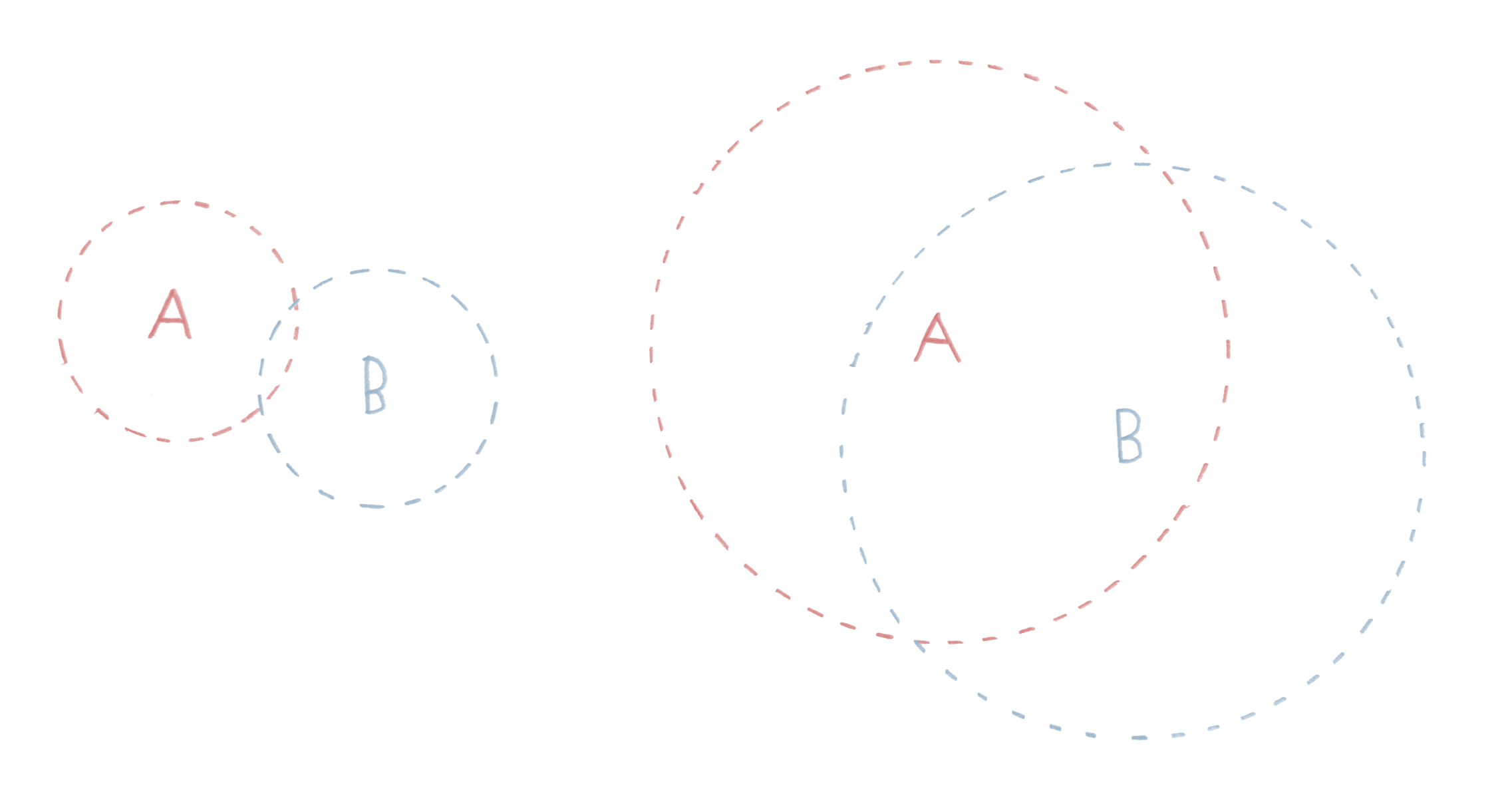

The lesson from Lewontin's Fallacy in genetics is that populations with overlap on individual traits may be clearly distinguishable when multiple traits are considered simultaneously:

Illustration from Woodley 2010

To see if this is true of opinion, I performed a principle component analysis on ancestry groups for the following GSS questions:

| Variable | Description | postmat | postmaterialist values | spkrac | allow racist to speak | eqwlth | gov't reduce income differences | gunlaw | require permit for gun ownership | helpnot | gov't do more or less in society |

|---|

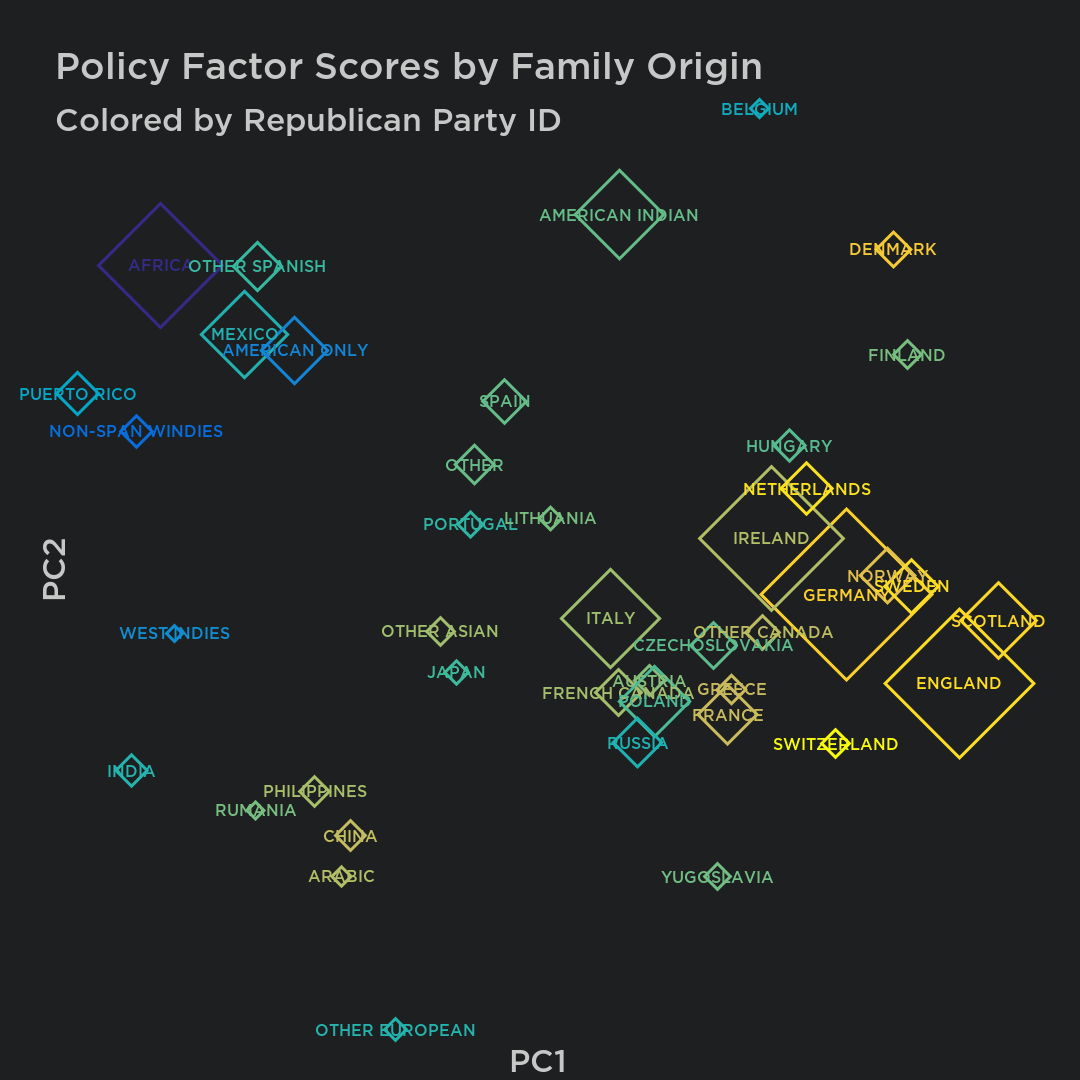

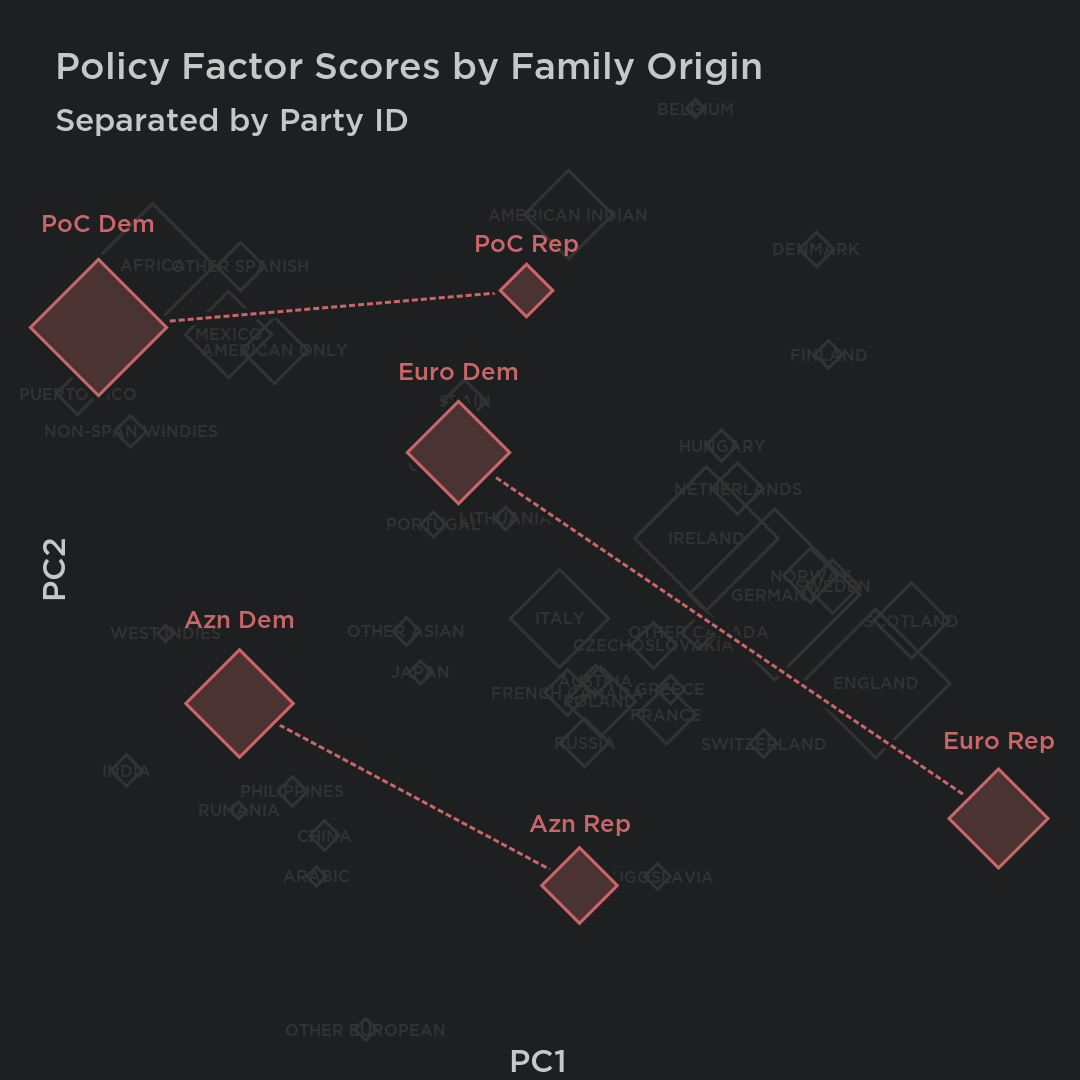

Two factors accounted for nearly 80% of variation, and the position of ancestry groups within them is as follows:

The result is an even more stark divide between European-Americans and PoC; Any possibility for overlap has been substantially reduced. Only the smaller, southernmost European nationalities occupy a moderate position.

The clustering also reveals interesting differences off the main axis of party ID. The assortment of continental Asian ethnicities that appeared moderate in terms of party politics are here seen as moving off in their own direction towards the lower-left, separate from both Europeans and the black/hispanic cluster. I don't know how to describe that difference in values at this time.

The strength of clustering can be seen by following a couple intermediate ethnicities at different stages of analysis: Mexico and Ireland, both of which are well-represented in the United States. At the level of party identification, Mexicans are closer to the Irish than Africans, by about 2:1 in partisan distance. But on the scale of economic opinion, they are slightly closer to African-Americans, and in the PCA, they have more than completely flipped to being six times further from the Irish as compred to blacks.

Apparent closeness of whites and PoC disappears in the context of clustered policy views.

In policy-space, one can leap from the most heavily Republican European ancestry, to the most Democrat, in only a quarter the distance it would take to reach Mexicans.

Even among the European ethnicities, partisanship is not as consistent as one might expect. If Polish-Americans were a state, they would be more than twice as Democrat leaning as California. But on policy questions that tend to separate Democrats from Republicans, they are comfortably adjacent to the moderate French-Americans, who would themselves be a swing state. And even the outlier Jewish backgrounds ultimately found their way back to clustering with the rest of European America.

This is not to say that all comparisons are all so stark. But it is to say that, when one looks at the gradient from Switzerland to Japan to Africa, it hardly suffices to describe the difference as one end of the spectrum being "more Republican" than the other. There is a deeper similarity among ancestries that cluster together.

Variation Within and Between

We've looked at partisan lean, and seen it's imperfect in describing the relative position of ancestry groups. But even with these fine groups, we're looking at averages of large populations. Sure, Europeans all tend to bunch up on policy relative to other groups, more than you would expect based on party id, but maybe this is a shallow finding, and there's actually substantial overlap between races beneath that.

A typical "overlapping curves" problem — given some average difference between groups A and B, how exclusive are the actual group members?

After all, every group will have its share of Democrats and Republicans, who might move far off in their own directions. What I wanted to investigate were the within-race political spectra. How different are white Republicans vs Democrats, in the scale of race differences?

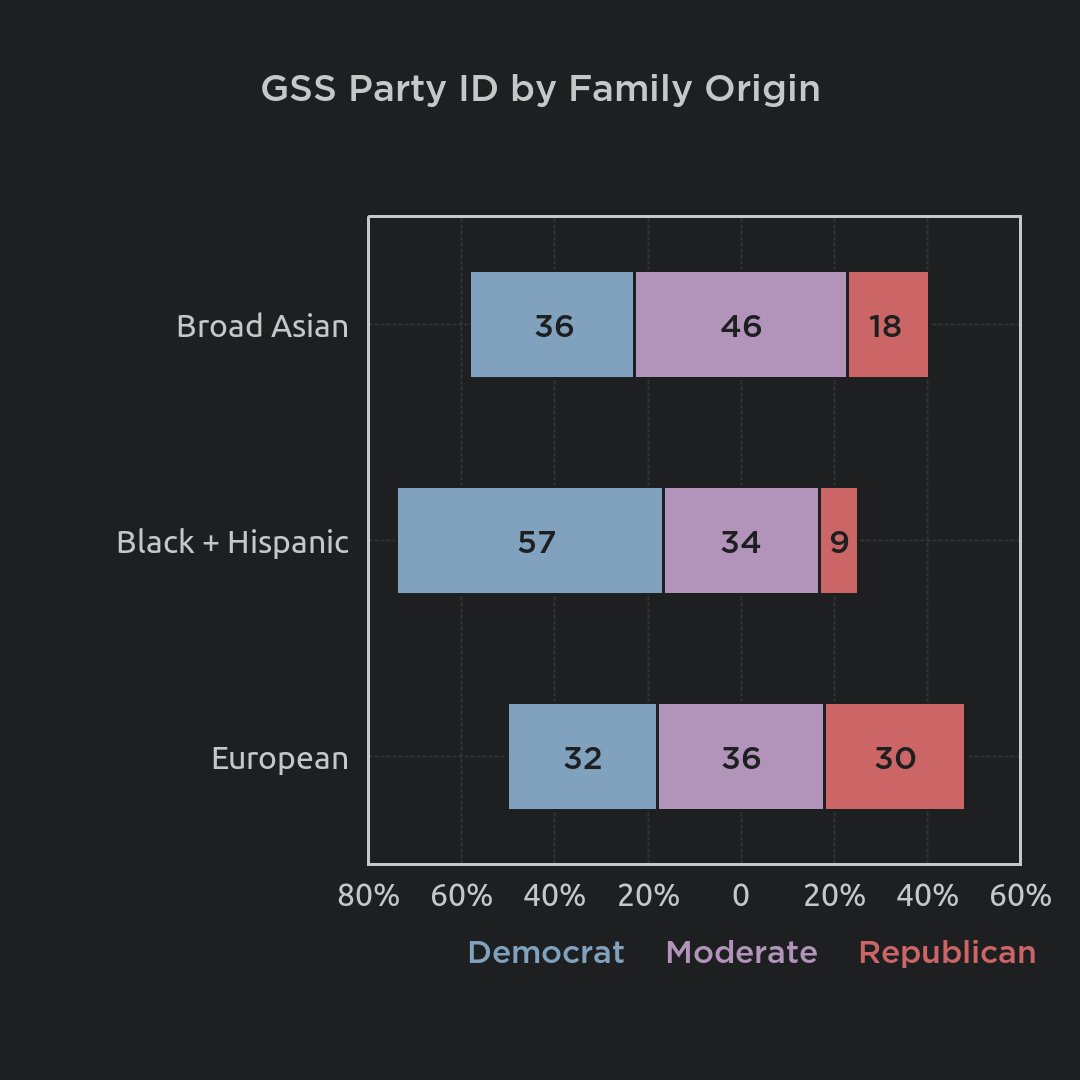

For reasons of simplicity and sample size, I combined ancestries into a few larger groups informed by the PCA: All Europeans, the PoC cluster from the top left, and the contiental Asians from the lower-left. I'm going to call "Democrats" those who identify as "moderately to strongly" Democrat, not merely Democrat-leaning. Likewise for Republicans. The resulting party identification for these broader groups is familiar:

"Asians" are 2:1 Democrat, and the brown cluster 6:1. Europeans split about even.

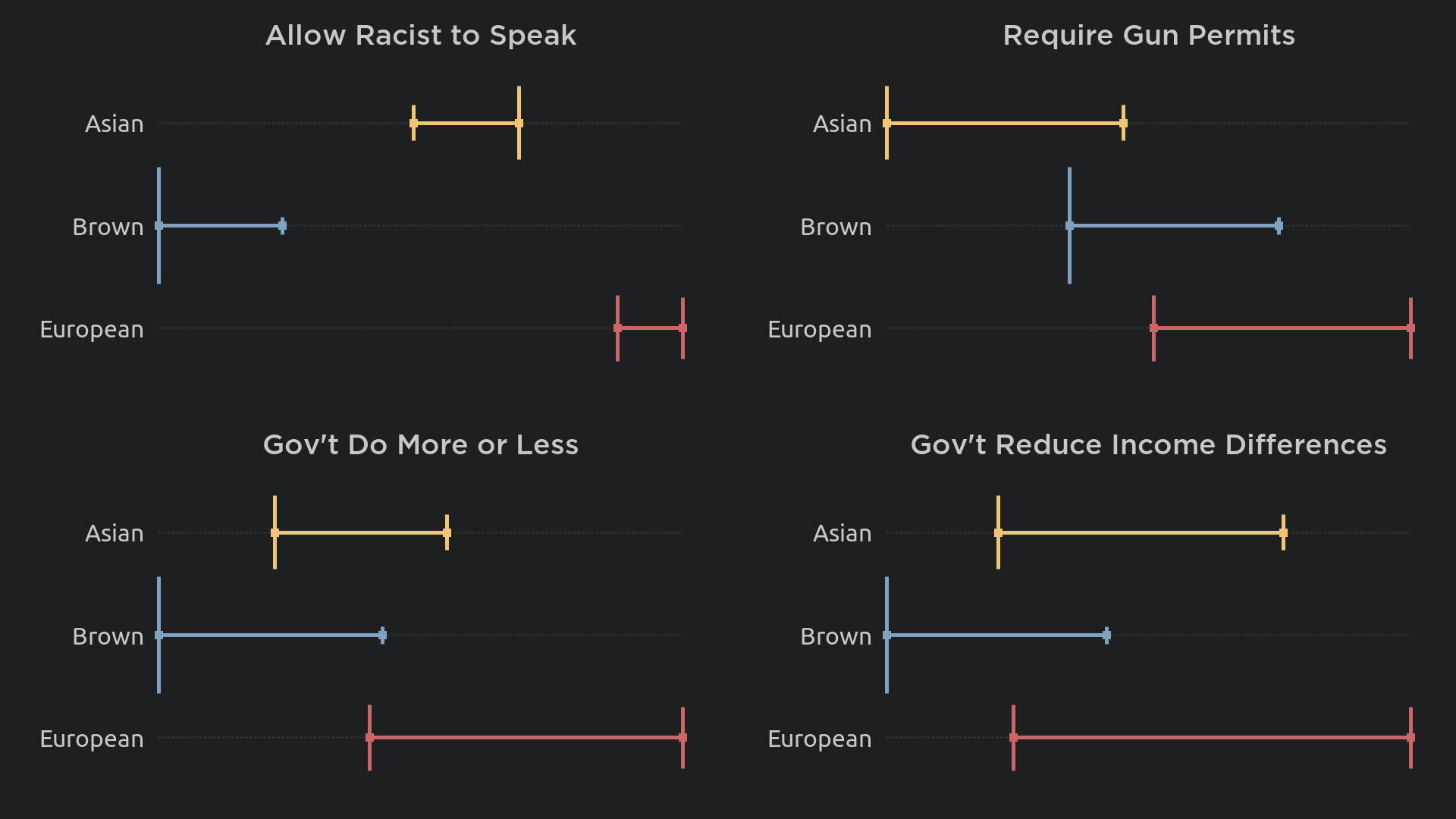

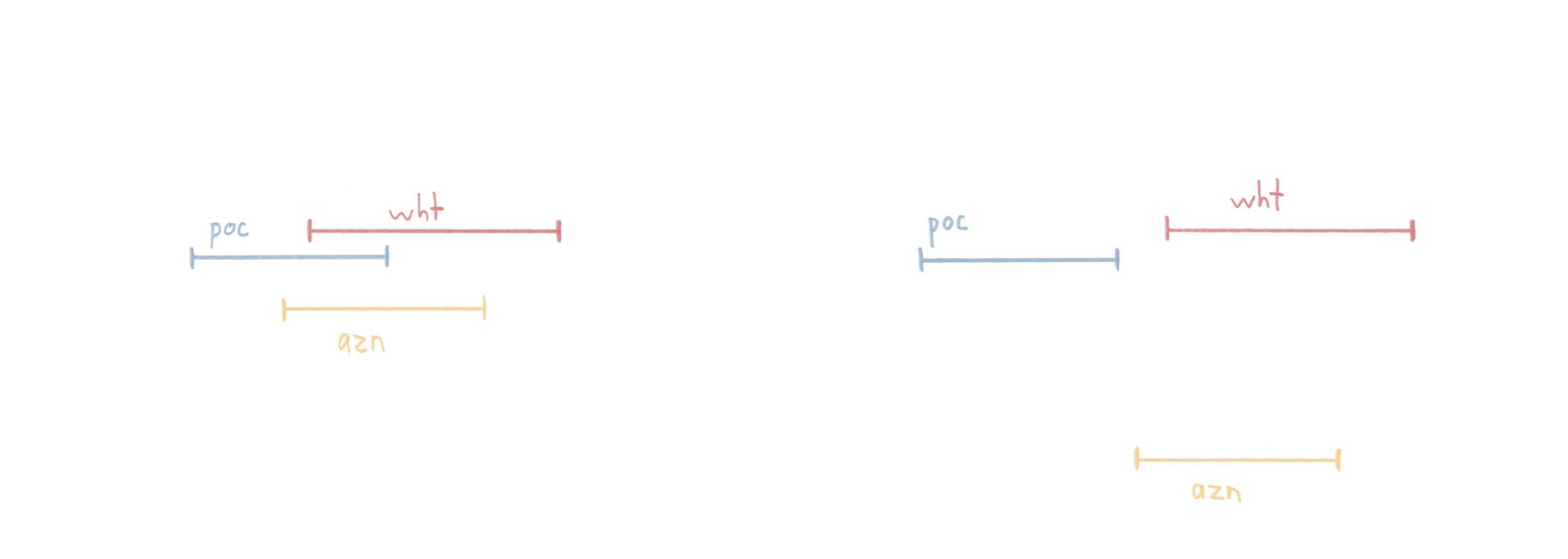

To depict the distribution of opinion within and between race, I decided to use something like a whisker plot. I'll draw a line for each group from the position of the average Democrat, to the average Republican. At each end of the line is a vertical bar sized according to the relative share of the group represented at this point.

How to Read the Lineplots

Each value is depicted with the "right wing" position towards the right.

Here are the ranges for our three groups, for the previous GSS questions:

The results were more striking than I expected. Even before performing any cluster analysis, there are issues with almost no inter-racial overlap.

- Free speech stands apart as having almost no between-party separation relative to between-race divides. Among the Asians, the partisan direction is reversed — I'd like to find other issues that are similiarly flipped.

- The median PoC — and almost all Asians — are less gun-friendly than the average European-American Democrat.

- PoC are mostly out-of-range on big government.

- The most overlap is on income redistribution, but even here the few PoC who identify as Republican are closer to white Democrats.

I'd like to look at more issues but I had to write this up at some point.

So maybe the party identification plot should actually look something like this, with the moderates of each group not really lining up with each other:

Assuming that it's even proper to line up these groups on a common axis of partisanship — Asians and PoC are both "left" of Europeans, but each in their own different direction.

Finally, I applied the PCA model from the nationality analysis to the party subgroups, e.g. "if white Democrats were their own national origin, where would they be on the map?" The result is this:

If nothing else, science confirms: Brown Republicans aren't really a thing. The range of European partisan opinion is large, but still almost entirely exclusive of the PoC distribution. The few PoC who do identify as Republicans have views similar to white Democrats. Republicanism also appears to mean something slightly different for PoC than it does for Europeans.

The broad Asian group is more interesting. Projected onto the European left-right axis, they would mostly overlap while being shifted considerably to the left. But the entire Asian opinion curve is also offset in some dimension orthogonal to US partisan politics. My tentative view is that this difference is related to individualism/self-expression values, which are not as strongly partisan among European-Americans. This model might describe how an Asian Republican can be a moderate on economics, but less hostile to restrictions on speech and gun rights.

Implications for group overlap are unclear. If we are going with the model of parties being defined along the axis of greatest variation, this would imply Asian opinion may be mostly exclusive of that of Europeans. (That is, if one imagines the party poles depicted on the map as the focal points of an ellipse, how eccentric is that ellipse?) How tight that group clustering is will require a better picture of the range of non-partisan intra-racial opinion.

Potential overlap in the minor axis of political opinion.

The Greyscale Picture RevisitedMy mental model of party identification in the United States looks something like this, incorporating both of the potential distortions of party politics discussed at the start of this post:

A Basic Model of Race vs. Party ID

There is a spectrum of party politics in America, and whites span much of it. Other races sort themselves into it with some degree of overlap, but this apparent blending is shallow. Range restriction obscures how far to the left of whites blacks and hispanics truly are, and dimension reduction obscures how Asian minorities have views different from traditional politics.

Conclusions for Now

This investigation proved sufficiently interesting that it was difficult to find a stopping point, so I regret the lack of a tidy resolution. I needed to stop myself trying to construct a unified theory of American politics. In the time I have been composing this, Last has posted another video elaborating his view of the non-uniqueness of European politics. I disagree with his interpretation of the data presented, but do not want to continue to expand the scope of this already-lengthy post further beyond the topic of party identification and broad opinion clustering.

I agree with Last that there is much party differentiation among European-Americans, but stress that this is to be expected in a political landscape long dominated by a white supermajority, and doesn't appear to be in the same scale of between-race differences. Although it was not the focus of this article, my research so far also confirms the Myth of Assimilation, and not just for Europeans. Among all ancestries, there is a strong correlation between values globally and within the United States. The melting pot finds little support in the data. This is particularly true once small, nonrepresentative ancestries are excluded.

Where I disagree with Last (and, by extension, Ryan Faulk, who has taken up a similar view) is on the relative distinctiveness of European politics. I find that:

- European-Americans are more uniformly right-wing on (economic) policy than party ID would suggest.

- Statistical investigation of opinion reveals a distinctly European cluster, obscured by partisanship and individual polls.

- Within-race differences are large, but the range of European opinion shares almost no overlap with PoC. Interpretation of the rising Asian minority is ambiguous.

However, I wouldn't take my view of the data so far as to lend support to a global white identity spanning all nationalities. Within the United States, the minor Eastern European ancestries clearly strain the boundaries of the "white" opinion cluster. This parallels similar maps of global opinion from the World Values Survey. At the extremes, the gap between Western Europeans and non-Jewish Russians truely does appear so great as to be comparable to between-race gaps. I am not eager to see such values merged into the American political mix unrestricted in order to satisfy a purity test of pan-whiteness.

The last point I'll make, which didn't fit anywhere else, is that there's more to political life than being a Republican. The specialness of Europeans, and of first world politics generally, is not that we are the Most Republican people in the world, or even the most "right wing", whatever that means in the big picture. Don't be distressed that white people aren't voting as a monolithic block, since that isn't even possible given their current share of the electorate. There is room for positive movement within the existing white vote, which will remain powerful for a long time.

This is not the first time I have had my opinions challenged by Sean Last. Years back, I recall listening to his videos at work, growing steadily agitated by his criticisms of libertarianism, which would become more persuasive to me in time. It is probably to my benefit that he is the one putting forward these critiques, which I would be less receptive to hearing from another voice. I think I'm mostly right this time, but look forward to more productive discussion.